Redefining displaced form

Redefining displaced form

Three new exhibitions have opened at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin. None of them are extraordinary, but all three contain documentary implications worth considering.

Part File Score is the title of a new sound installation by Berlin-based Scottish artist Susan Philipsz (b. 1965), the latest in a string of artists who, since 1999, have yearly been invited to ‘Works of Music by Visual Artists’ — a series of exhibitions where the connection between visual and acoustic experience is an integral element of participating artists’ work. The combination of the three words ‘part’, ‘file’, and ‘score’ initially gives the impression of a play on words regarding different kinds of documents in the sphere of music and their meanings, but it’s actually a rather simple summation of the basic premise of the piece, in a very direct and straightforward way. In the historic main hall of the old railway station, she has placed 24 loudspeakers. There are 12 on either side, all of which play a different tone, i.e. each loudspeaker is assigned a tone on the chromatic twelve-tone scale, so that each voice echoes around and through the big hall. These parts are based on three film scores by German composer Hanns Eisler (1898-1962), who was forced to leave two countries during his lifetime: first, Germany in the 1930s due to the Nazis, and then the US due McCarthyism in the 1950s. Behind the loudspeakers, on either side of the hall, are 12 large prints of pages from the scores being played, and these scores are overlaid with pages from Eisler’s FBI files.

In a sense, it’s a soothing feeling of refreshing simplicity, moving about the restored and polished hall, listening to the engineered and polished 24-channel spatial sound installation. But that is all. This piece is about parts, files, and scores. The visual and auditory result is well executed and even somewhat beautiful, but what you hear is what you hear, and what you see is what you get. No more, no less. And within the domain of art, one-to-one correspondence is problematic, because of the inherent reduction of meaning. If you, as an artist, strive to cut off all potential links to the goings-on of the outside world and strictly examine concepts, like a composer basing an entire musical composition on a certain interval, then you restrict the possible implications of the work.

But (officially), Philipsz is claiming something beyond the immediate visual and acoustic experience. This is what we expect from a visual artist of today, but it’s in this strain to go beyond — into symbolism, politics, or drama — where this piece fails to become more than its obvious single layer. According to the artist herself, she ‘attempts to convey Eisler’s aesthetic of displaced form while touching on themes such as life’s journey and the experience of surveillance, separation and displacement’, and ‘draw a parallel between the train station as a place of departure and arrival, of separation and return, and the moved life of the composer Hanns Eisler’. That is nonsense, due to the simple fact that it’s not implemented in the work; there’s no connection between the visual and auditory experiences, other than that we know it’s Eisler’s music playing. If her wish was to give artistic form to concepts like separation and displacement, and specifically in dealing with Eisler, who was exiled and deported twice in his life, then we have to question her work’s complete absence of harsh experiences — resistance, misery, mistrust, alienation and fear — which I think would have dominated these specific periods in his life.

Displaced medium for waging war

Harun Farocki (b. 1944) is a German filmmaker who has been investigating issues relating to the psychological, social, and political impact of audio-visual media since the late 1960s. Specifically, how images of war presented to the public have changed over the decades by replacing old photographic media with new technology which displays moving images. According to Farocki, there is an obvious development in how moving pictures were shown to the public. It started off with newsreels during World War II, then there was the Vietnam War, which was the first war to be televised and thus brought into American living rooms. The first Gulf War was also heavily televised, but with the addition of new video satellite technology, which gave us live coverage (the CNN factor). During the second Gulf War (Iraq, 2003), the internet had its major breakthrough: international news websites provided online coverage of so-called top stories only hours after the war began.

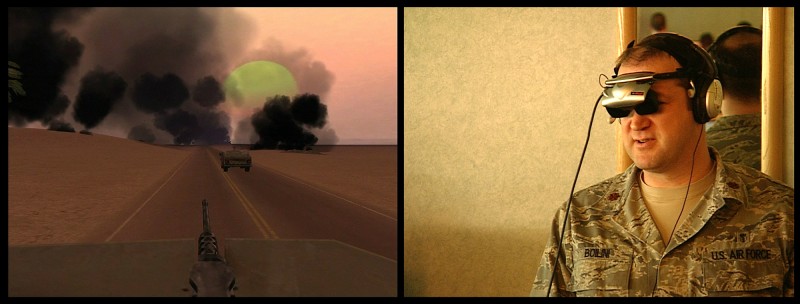

In his latest work — four video projections entitled Serious Games — Farocki investigates whether computer game technology is the future means of waging war. Currently, in the US, game developers play an important role in all steps of warfare. They have already created virtual Vietnam scenes and situations to help traumatized veterans. Nowadays, they construct similar reproductions of countries like Iraq and Afghanistan, where young recruits can engage in combat training. In Serious Games I: Watson is down, on one half of the screen, we see some young soldiers in uniform sitting in front of their computers, and on the other half, the scenes they are reacting to. This is initially very effective, because I immediately think that these people are in a real situation, and it’s only after some time I realise that the soldier named Watson, who is suddenly shot dead, is actually the real-life Watson sitting in front of the computer. The four videos are fascinating as well as worrying; they raise questions concerning the concept of Hyper-reality, and ask whether the stereotype of a typical enemy, which the US Army claims as hard fact, is even subject to debate anymore. The strongest part of the experience, though, is that Farocki emphasizes the absurdity of these situations by never explaining or commenting them.

Redefining the wall

The exhibition Wall Works offers work by 34 late modernists and their approaches to the white cube and their struggles with the wall. In the museum’s enormous Rieckhallen, this exhibition shows work by artists who, since the 1960s, have been working abstractly, minimalistically, or conceptually with the wall as a carrier of images in a defined and restricted space. The space is examined in several senses, incorporating various materials, such as silkscreen, wallpaper, spray paint, wood, steel, and glass, and employing techniques and media ranging from painting and drawing, light projection and written text, to sculptural floor-, and wall objects, and video work. The quality of the different pieces in this group exhibition fluctuates between occasionally highs and (more often) lows, but can still easily be recommend due to its historically informative qualities. If you’re interested in an overview of how artists over the last five decades have used the wall to define space, then this ‘time document’ is really worth a visit.

There are, of course, some works that stand out. In 1965, Joseph Kosuth (b. 1945) created several pieces that were philosophically based explorations of the nature of art: among them are One and Three Chairs, Glass (One and Three), and Wall (One and Five). The latter consists of four white canvases and an empty space for a missing fifth. Three of them present a description of the words ‘wall’, ‘white’, and ‘plaster’, the fourth is empty. And as with the other works of Kosuth — as an antithesis to an obvious explanation of the actual objects — he doesn’t say that this is what it is. Instead, he points out that a connection is formed between him, the object, and the observer. The definition is twisted and nothing is actually defined. Instead, by playing with the definition, Kosuth questions what we actually observe — an established, so-called truth is brought into question, becomes a negation, and is thus set in motion within our minds.

In the same year as this series of works were created, Monica Bonvincini was born. Her video work Hammering Out is on display in the room next to Kosuth’s. This curated juxtaposition provides a clever interplay between the two, as while you contemplate Kosuth’s work, there’s an obtrusive banging sound coming from the inner room, which turns out to be amplified sound from her video piece, where you see a female arm attacking a (white) wall with a sledgehammer. Presumably, this work has more than one layer, when we consider her other pieces, several of which deal with issues concerning gender and class, but in this thematic context and next to Kosuth, it’s hard not to think of her statement about the conceptual foundation for apparently neutral spaces, such as the white cube: ‘For me, there is no such thing as a neutral architecture. Nothing is neutral, from the moment you open a door and go in somewhere.’

Redefined self-perception

During my visit, I opened a glass door at the very far end of Rieckhallen, thinking it would lead me to the restrooms. Entering a large, dark room, I first thought I had entered one of the museum’s storerooms, when I noticed that it was totally empty except for a black architectural sculpture set in strange, vague lighting. At a distance, I could see it was three interlinked corridors. When I entered one of the two horizontal corridors and walked to the very middle, I was suddenly standing on a metal grid where the corridors met. Looking down through the grid, I could see a dark empty hole, and an uncomfortable feeling came over me, mainly because of the unstable metal grid I was standing on, but also due to the uncertainty of where I actually was and what it all meant. When I looked up, I saw the same empty, black space extending upwards, and that’s when I realised that this sculpture was made out of three corridors, and that the space consisted of nothing. Nothingness.

Room with My Soul Left Out, Room That Doesn’t Care by Bruce Nauman (b. 1941) belongs to the museum’s permanent collection, and it’s somewhat unclear whether it’s connected to the exhibition or not. But I still wanted to mention it because it generates mixed feelings of entrapment and debarment, and it surprises me that an architectural sculpture in a museum can have such a powerful impact. But it does. And what this work really offers is an existential experience of desolation, which in some senses reminds me of Daniel Libeskind’s visual and spatial language with the history and symbolism substituted with existential entrances, raising questions about ourselves and our positions in life. This experience is presumably what is lacking in the majority of the other works in the exhibition proper, which I feel are only a conglomerate of variations on a static existence, where the only movement is from one point to a similar point. Nauman has proved that it’s possible to explore and invoke existentialism in art — initially, by placing the viewer in an uncertain situation, with an unclear purpose and only a vague sense of searching for something, followed by a tactile element and the notion of a distant presence, ending with that moment of focus and universal simultaneity.

KunstForum 03.03.2014