The Dismounted Heaven

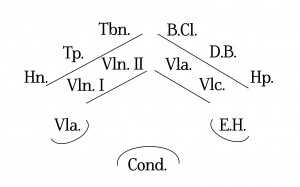

Ensemble

Horn in F

Trumpet in C

Trombone

Bass Clarinet

Double Bass

Harp

Violin I

Violin II

Viola

Violoncello

The Dismounted Heaven

“Ever since childhood, the Book and the Journey have had an attractiveness on me, […] they become a part of the story of your own life.”

In 2011, the Swedish author Peter Handberg (b. 1956) released a selection of essays written between 1997-2009 about authors, books and journeys, which have made a persisting impression on him – books initiating a trip, the trip leading back into the books.

In a commando bunker on a deserted rocket base outside Võru in southern Estonia, Handberg finds a “travel writing” that has a major existential impact on him, despite the fact that it doesn’t contain one single comprehensible sign. A long, white paper strip – 200 meters when unfolded – had been left behind on a table next to some telegraph keys. The white strip that was cabled out of the machine, contained codified information, such as: ATE 643 or XYT 921. The Soldiers in the bunker activated the gyro system, the nuclear charge at the top of the missile was programmed to explode on an approximate height of 500 meters above the target and – via a simple manoeuvre – the ultimate disaster would be a fact.

The missile was charged and ready to take off. But where? Nobody on the base, not even the officers in command, knew what these codes meant, but they could assume the possible destinations based on the amount of fuel and the gyro settings: maybe London, possibly Paris, presumably several destinations in former West Germany. These insignificant and unclear signs was apparently a carrier of a technical subtle and intricate system, where in the possibility to extinct entire nations in no time was at hand. According to Handberg, this white paper roll was an existential writing in the deepest of meanings – incomprehensible and mystical as well as clear and terrifying.

A couple of months after returning from Estonia, he coincidentally finds his forgotten souvenir in the bottom of a suitcase, and then suddenly sees a possible connection. He gets on a plane to Firenze, Italy and the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo, to see a sculpture, which several years before had left an enigmatic impression on him – Donatello’s The prophet radiates “one of the most affecting expressions in the spectra of human depth”. The prophet is holding a roll lightly leaned against his hip and the look in his face “could indicate contemplation on the eternal questions in life regarding the totality in our world”.

According to Handberg, everything is written in the roll, and he now understands why the expression in the prophet’s face – simultaneously revealing clear insight and profound pain – had made such a major impression on him over the years: The prophet has always known that one day mankind no longer exist, he knows that his roll contains the codes of total destruction and that the beginning and the end is carved out in stone.

Five hundred years later, in the woods of southern Estonia, these codes rustled out on another roll, missiles that were able to destroy the entire earth were prepared, and the prophet knew it all from the beginning. He had read the writings backwards and thus realised the entropic character of time and the slowly sinking ceiling above mankind. The contact between heaven and earth was about to be cut, the inhabitants of the earth were about to take the final leap out of themselves and dock the machines for good – the heaven was about to be dismounted.

Program Note

”My dream is the dream of free arrangement, the dream of the lucky hand, the dream of unbroken composing. I want to sing as the bird sings that lives in the branches. However, we are living in the branches of a dying forest.”

The quote is taken from an interview with Helmut Lachenmann, in which he was asked to explain his relationship to music history in general, and to – what the journalist refers to as – “contemporary music’s lacking beauty” in particular. His answer is a poetically precise description of the non-musical parameters that the contemporary composers have to relate to, as well as a key to his own musical universe. The metaphor is obvious and dystrophic – it’s the basis of a collapsing music, a black hole is expanding and the earth cracks.

The critics of Lachenmann – headed by Hans Werner Henze – called him a nihilist; the music communicated nothing but denial. Audiences and orchestras rejected the “awful” music, and Lachenmann was treated roughly during this period. His friends tried to stand up for him by claiming that his music was consciously “awful” since this was primarily a revolt towards the bourgeois beauty. Lachenmann himself denied that: “It’s still beautiful, but in another way. Beauty is not a standardized category, beauty is to overcome standards.”

My personal listening experience of the music is neither “awful” nor “beautiful”. In the major part of his works, there’s initially a certain amount of resistance, which for that matter you’re able to overcome by repeated listening, but for me, the power of his music is partly due to the aesthetic and socio-political reflections he has been occupied with during almost half a century. When these modes of thinking are transformed into compositional principles, the result becomes multilayered and there are so many parameters you can brace yourself against. It can in other words be both awful and beautiful; it can radiate a clear state of the calm-before-the-storm as well as a strong notion of the after-the-catastrophe.

When reading about the deserted missile base and the prophet with the sad face – simultaneously revealing clear insight and profound pain – I came to think about birds that sing in the branches of a dying forest and ruin music, and decided there and then to find my own references to an accompanying timbre, based on my personal relationship to our age and what sonority connected to beauty and “awfulness” means to me.

In most of my earlier works, I’ve been occupied with classifications and analysis of the history of western music; researching processes about specific composers or works, where in a specific expression or gesture was of certain interest, which have resulted in very planned and controlled compositional processes. In this case, I have gone through the opposite while trying to accomplish the ”dream of free arrangement, the dream of the lucky hand, the dream of unbroken composing”. And here’s the result.

The timbres went quite naturally and immediate through transformations and deformations. And the sounding result became for most parts satisfying, with the two solo instruments – in a broken dialogue – leading the others, not towards the end which you might imagine, it’s rather an energetic but still standing music where the dark and irrevocable hangs around like a persistently glimmering star of darkness.

Duration

10 min.